Review these files, to follow along Mr. Neufeld’s case.

| Application to Adjourn | Application to Adjourn Supporting Affidavit |

| Barry’s Reply Submissions To The Complainant’s Response To Our Application To Adjourn |

| Letter Drafted In Response To The Complainant’s Lawyer’s Email Of Friday Evening (Sept. 27) |

Application To Adjourn

September 20, 2024

This is the _____ affidavit of

Barry Neufeld in this matter

and was made on 20/SEP/2024

Case No.:CS-001372

At the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal

In the Mater of British Columbia Teachers Federation obo Chilliwack Teachers Association v Barry Neufeld

AFFIDAVIT

I, Barry Neufeld, of _______ British Columbia, SOLEMENLY AFFIRM AND DECLARE THAT:

1. I am the respondent in the above-noted matter. I have knowledge of the matters to which I hereinafter dispose, or am advised by counsel, in which case I verily believe the same to be true.

2. This is a complex case with a prodigious volume of materials and multiple witnesses, amounting, respectively, to approximately 74 gigabytes of digital files, including over 500 documents and dozens of hours of school board video footage; and approximately one dozen lay witnesses and at least one expert witness.

3. I was represented by David Bell and Shauna Gersbach of guild Yule LLP until February 2024, at which point my professional liability insurer discontinued funding my legal representation, and Mr. Bell and Ms. Gersbach withdrew. Mr. Bell and Ms. Gersbach required a $150,000. retainer to represent me privately, which I could not afford.

4. I was granted an adjournment in June 2024, to retain counsel, but my efforts were unsuccessful until September 18, 2024. Between June 2024 and September 18, 2024, I approached the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms, Freedoms Advocate, the Democracy Fund, and Paul Jaffe. The Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms and Freedoms Advocate rejected my case, and I have not heard back from the Democracy Fund to the present day. Mr. Jaffe had hearing date conflicts and was unable to assist me in this matter.

5. On September 18, 2024, I retained James SM Kitchen, a sole practitioner in Alberta.

6. I am informed and do verily believe that Mr. Kitchen has no paralegal; his legal assistant is presently on maternity leave; and he has one associate, a two-year call, with almost no availability until December due to her enrollment in mediation courses and impending hearings.

7. I am informed and do verily believe that, while Mr. Kitchen has no hearing dated conflicts between October 21 and November 1, 2024, per se, he runs a busy practice with numerous open files and their attendant deadlines and hearings, and therefore has insufficient time to prepare between now and the commencement of the hearing on October 21, 2024.

8. I make this affidavit bona fide and for no improper purpose.

Next Hearing Date:

On May 21 the BCHRT said they would deliver their decision within the next six months.

It was announced that they will not deliver until Jan/Feb 2026.

Consider a Donation

Application to Adjourn Supporting Affidavit

September 22, 2024

Case No.: CS-001372

At the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal

Between:

BRITISH COLUMBIA TEACHERS FEDERATION

OBO CHILLIWACK TEACHERS ASSOCIATION

Complainant

and

BARRY NEUFELD

Respondent

APPLICATION PARTICULARS

James SM Kitchen

Barrister & Solicitor

203-304 Main St S, Suite 224

Airdrie, AB T4B 3C3

T: 587-330-0893

james@jsmklaw.ca

Counsel for the Respondent

Lindsay Waddell

MOORE EDGAR LYSTER LLP

Counsel for the Complainant

FACTS

1. Barry Neufeld is the Respondent to a complaint filed by the British Columbia Teachers Federation obo the Chilliwack Teachers Association. The hearing of the complaint has been set down for October 21- November 1, 2024.

2. The case is both factually dense and legally complex. Over 500 documents and 100 hours of video footage have been disclosed by the complainant. The issues span multiple areas including publication, employment and retaliation. A Charter analysis will be necessary. Some dozen witnesses are expected to be called, including at least one expert witness.

3. Mr. Neufeld has been unrepresented by legal counsel for seven months. While Mr. Neufeld had been represented by David Bell and Shauna Gersbach of Guild Yule LLP, in February 2024 his professional liability insurer discontinued funding his legal representation, and Mr. Bell and Ms. Gersbach withdrew. Mr. Bell and Ms. Gersbach required a $150,000 retainer to continue Mr. Neufeld’s representation, which was untenable.

4. Mr. Neufeld set about trying to find alternative counsel, which proved nearly impossible, given his limited means in combination with either lack of interest in his case or lack of availability to provide representation. Mr. Neufeld approached the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms, Freedoms Advocate, the Democracy Fund, and Paul Jaffe—all of whom declined.

5. Mr. Neufeld retained James SM Kitchen, a sole practitioner from Alberta, after close of business on September 18, 2024 (10:17 PM PST, to be precise). The next day, Mr. Kitchen worked quickly to contact opposing counsel to inform her he was on the file and would be requesting an adjournment, and to seek her client’s consent to an adjournment.

6. While Mr. Kitchen is willing and able to assist Mr. Neufeld, he operates a busy litigation practice, currently without the aid of his legal assistant, who is on maternity leave. Mr. Kitchen’s associate, a 2-year call, has almost no availability to assist him until December, given she is completing coursework toward a mediation designation and has deadlines on her own files and impending hearings. Mr. Kitchen has many open files with their attendant deadlines and hearings between now and October 21.

LAW

Tribunal Rules

7. Rule 30 of the BC Human Rights Tribunal Rules of Practice and Procedure provides that an application for an order adjourning a hearing must be filed at least two full business days before the date set for the hearing; must state why the request is reasonable; and must state why granting the request will not unduly prejudice the other participants.

Tribunal Precedents

8. Factors influencing adjournment decisions include the circumstances surrounding the transfer between counsel; the amount of time since counsel was retained; the sufficiency of the time remaining to prepare; whether counsel is in fact changing or simply being added; the complexity of the case; the volume of materials; whether counsel is a sole practitioner; whether counsel sought adjournment in a timely fashion; whether counsel sought the consent of the opposing party; the degree of control counsel had over setting the existing hearing dates; the age of the matter; factors limiting the client’s representation options, such as finances and difficulty finding counsel; the motivation for the adjournment; whether the loss of counsel was voluntary; whether any prejudice claimed by the objecting party is real or merely speculative; and which party would be more prejudiced as between granting or not granting the adjournment.

9. Where adjournments have been denied, such factors have militated against the reasonableness of granting adjournment. For example, in Hussey v Ministry of Transportation, 2003 BCHRT 15, “the Tribunal did not grant the adjournment because: there was an internal transfer of files between Ministry counsel; the hearing was some two and [a] half months away; [and] the first instance of discrimination alleged by the complainant was almost eight years before” (Wakelin v White Oaks Futures Ltd (cob Ellwood Animal Hospital), 2004 BCHRT 405 [Wakelin] at para 20).

10. The adjournment in Weisner v BCO, 2003 BCHRT 18 was denied because counsel had been retained 14 months prior to the scheduled hearing and the file was not being transferred to new counsel, rather co-counsel was joining the matter (Wakelin at para 21).

11. The adjournment in Yates v Ross, 2004 BCHRT 83 was denied because counsel took the file knowing he would be on paternity leave during the hearing and his organization had been involved in setting those hearing dates in the first place.

12. On the other hand, in Wakelin, a case wherein an adjournment was granted, the respondents had difficulty retaining counsel for want of resources; the Law Centre withdrew from the case against the wishes of the respondents; the change of counsel was not motivated by a desire to delay; proceeding with the scheduled dates would have unduly prejudiced the respondents; and short of losing witnesses or negatively impacting the merits of their case, the complainants faced mere inconvenience and not undue prejudice (at paras 24-5). Having “already booked time off work to attend the hearing” and “summonsed witnesses to attend”, as well as desiring the complaint to proceed in an expeditious manner do not constitute undue prejudice (Wakelin at para 17).

13. In Doratty v Fording Coal Ltd, 2004 BCHRT 82 [Doratty], an adjournment was granted on the following bases: the plaintiff’s representation options were limited (at para 14); counsel acted in a timely fashion, seeking consent from the respondents’ counsel within three weeks of being retained (at para 16); and the prejudice identified by the respondents—namely that “witness memory and availability” would be impacted by a six-month delay—was found to be speculative. The Tribunal stated that the delay, while “of some significance”, would not unduly prejudice the respondents (Doratty at para 18).

The Tribunal characterized the prejudice to the plaintiff, however, as “grave” should her adjournment be denied, owing to the complexity of her case, which the Tribunal described as “factually involved and legally complicated” (Doratty at para 19). The Tribunal stated that “expediency cannot be at the expense of the overall fairness of the process or at such a significant cost to one of the parties” (Doratty at para 19). In Clarke v Lou’s Rent-All Service Ltd, [1994] BCCHRD No 5, the Tribunal found that the length of the adjournment to permit new counsel to prepare depended on the complexity of the case (at paras 5, 8).

14. In Petterson v Gorcak, 2008 BCHRT 260, the Tribunal granted an adjournment on the bases that while “parties to a complaint are not required to have counsel…if they wish to be represented, that is their right” (at para 19); the only counsel the complainants were able to retain could not represent them absent an adjournment (at para 19); and the ability of witnesses to participate if the hearing were postponed would not unduly prejudice the respondent (at para 21).

15. Sinclair v Blackmore, 2004 BCHRT 433 found the Tribunal granting an adjournment premised on counsel for the respondent’s status as a sole practitioner who could not reconcile the hearing dates with his schedule, as well as the fact that he had sought the complainant’s consent to the adjournment more than one month in advance of the scheduled hearing dates (at para 5).

16. The Tribunal granted an adjournment in RR v Vancouver Aboriginal Child and Family Services Society, 2022 BCHRT 116 for the express purpose of affording new counsel “the opportunity to get up to speed” (at para 433), given the volume of materials he was obliged to review (at para 435).

17. In Stentaford v Westfair Foods Ltd., 2004 BCHRT 81, wherein counsel “notified the respondent immediately after being retained that it was not available for the hearing dates and requested an adjournment”, the adjournment was granted despite the opposing party’s concerns regarding prejudice because they were found to be “speculative”: “the respondent had not…identified any individuals about whom this concern applied. As a result, the Tribunal concluded that the respondent would not be prejudiced by a short adjournment” (Wakelin at para 22).

18. Even where legitimate prejudice existed, i.e. out-of-town witnesses who had already paid airfare and accommodation expenses, “undue” prejudice did not issue and the adjournment was granted (Soriano v VTech Telecommunications Canada Ltd, 2007 BCHRT 244 at paras 12, 14). Delay alone did not amount to undue prejudice (Kennedy v Design Sportswear Ltd, 2001 BCHRT 42 at para 35); the prejudice to a party in having to proceed to a hearing without counsel outweighed the prejudice to the opposing party by reason of the adjournment (Cook v Citizens Research Institute, 2000 BCHRT 28 at para 27); and where new counsel stepped in and needed time to prepare and the adjournment did not add significantly to the delay in processing the complaint, the adjournment was granted (Aimers v Spirit West Construction Ltd, 2005 BCHRT 385 at paras 3-5).

ARGUMENT

Reasonableness of Adjournment

19. Mr. Kitchen is new counsel from a new firm, as distinct from substitute counsel from an already retained organization or additional co-counsel. Mr. Kitchen came on the scene 2 business days before this adjournment application has been submitted, sought consent for this adjournment as his first priority, and when unsuccessful, proceeded to prepare this application with all haste, including over the weekend of September 21-22. Mr. Kitchen will be acting in his sole capacity, which is to say, largely without staff, until near the end of the year. Neither Mr. Kitchen nor his firm had any control over anything that occurred in this case prior to now, let alone fixing the hearing dates.

20. The complexity and volume of this case, encompassing issues of publication, employment, retaliation and Charter freedoms, as well as lengthy witness lists, thousands of pages of documents, and dozens of hours of video recordings, combined with the preceding considerations regarding counsel’s circumstances and the successive considerations regarding Mr. Neufeld’s circumstances weigh heavily in favour of granting an adjournment to permit adequate time to prepare and ensure fairness to a party who has already been prejudiced by lack of counsel these many months.

21. Mr. Neufeld has no improper motive for seeking adjournment. Parting with his former counsel was not Mr. Neufeld’s choice, and he had a great deal of trouble finding new counsel both whom he could afford and who would be willing to provide representation on a matter of this magnitude. Not only will the respondent suffer no undue prejudice— the month-long notice of this adjournment constituting sufficient time to make scheduling adjustments and the short delay constituting insufficient time to significantly impact the overall resolution of the complaint; Mr. Neufeld stands to suffer grave prejudice should his new counsel be barred from preparing adequately such that Mr. Neufeld is able to meet the case against him.

22. On the foregoing bases, not only is Mr. Neufeld’s request for adjournment reasonable; an adjournment short in duration is the only reasonable course of action given the particular circumstances of Mr. Neufeld, Mr. Kitchen, and this matter generally.

No Undue Prejudice to the Complainant

23. The hearing being online, the parties having ample time to modify scheduling, the requested adjournment being of short duration, no individuals who might be prejudiced having been identified, the adjournment in no way negatively impacting the merits of the complainant’s case, the general dearth of practical implications resulting from the delay, and fairness being no slave to expediency in any event, no undue prejudice will accrue to the complainant by the granting of this adjournment.

REMEDY

24. Mr. Neufeld seeks a short adjournment of a minimum of 6 weeks to permit his newly retained counsel to prepare for what will be a complex and lengthy hearing. His counsel will make all efforts to be available for any proposed dates that are amenable both to the Tribunal and counsel for the Complainant.

25. In the alternative, should an adjournment not be granted, Mr. Neufeld seeks an extension to October 9, 2024 to submit his witness list.

September 22, 2024

Next Hearing Date:

On May 21 the BCHRT said they would deliver their decision within the next six months.

It was announced that they will not deliver until Jan/Feb 2026.

Consider a Donation

Apply Submission: Barry’s Reply Submissions To The Complainant’s Response To Our Application To Adjourn

Case No.: CS-001372

At the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal

Between:

BRITISH COLUMBIA TEACHERS FEDERATION

OBO CHILLIWACK TEACHERS ASSOCIATION

Complainant

and

BARRY NEUFELD

Respondent

ADJOURNMENT APPLICATION REPLY

James SM Kitchen

Barrister & Solicitor

203-304 Main St S, Suite 224

Airdrie, AB T4B 3C3

T: 587-330-0893

james@jsmklaw.ca

Counsel for the Respondent

Lindsay Waddell

MOORE EDGAR LYSTER LLP

Counsel for the Complainant

Complainant’s Cases Distinguished

- The starting point is that the Complainant, in attempting to distinguish the Respondent’s cases, appears to assume that any factual difference distinguishes a precedent. However, fact differences do not eliminate abstract principles the Tribunal observes. The ratio that delay alone does not amount to undue prejudice remains intact. The ratio that prejudice to a party in having to proceed to a hearing absent sufficient preparation may outweigh the prejudice to the opposing party by reason of the adjournment remains intact. The ratio that where a short adjournment does not itself add significantly to the delay in processing the complaint, no undue prejudice issues remains intact. The ratio that prejudice to the party opposing the adjournment will only constitute undue prejudice in extreme circumstances remains intact. The ratio that where prejudice is merely speculative, it will

not constitute undue prejudice remains intact. Three pages could not contain the examples of abstract principles that remain intact in this case despite factual differences in Tribunal precedents. The Tribunal is urged to be cautious to distinguish between outcomes that turn solely on facts and ratios that stand alone—the latter of which are numerous. - The next problem comes into sharp relief when viewing the context around the propositions the Complainant attempts to isolate for its purposes. Time does not allow a comprehensive review of each and every case in which the Complainant has engaged in this practice, but a few highlights are useful.

- In Street v BC (Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General) (No. 2), 2007 BCHRT 187 [Street], the adjournment applicant delayed in applying to the BC Human Rights coalition for over three months. Her failure in this regard is precisely what the Tribunal characterized as a “lack of diligence”:

While she maintained that she would only require a short adjournment as she would contact the Coalition immediately, her lack of diligence in her past efforts to pursue her complaint do not reassure me on this point: see Street. Further, Ms. Street first referred to her intention to file an application for adjournment in a pre-hearing conference I held with the parties on November 15, 2006. I referred her to the Tribunal’s website to find the necessary information and form to use. No application for adjournment was filed (at para 13).

The Street Tribunal’s finding of a “lack of diligence” stemmed from established facts around the Street complainant’s proven lack of diligence, not presumptions or guesses. - The Street complainant also failed to specify the duration of her requested adjournment; unlike in the present case, there was no certainty as to when the Street hearing might proceed: “[T]he lack of certainty of the length of an adjournment prejudices the Ministry” (at para 15). Mr. Neufeld is one Tribunal conference away from everyone knowing with certainty when the hearing involving him will proceed.

- Since the Complainant brings up Rostas v Llanes and others (No. 3), 2007 BCHRT 169 [Rostas], it is only fair to look at the entire case and determine what it stands for as a whole.

- Rostas contains a helpful discussion of prejudice, and affirms the Respondent’s contention that where prejudice is speculative, it will not constitute undue prejudice:

40 The Respondents assert that Mr. Llanes “has been experiencing great stress due to waiting for the resolution of this complaint”. In his affidavit, Mr. Llanes states: “I have an ulcer which has recently worsened due to my stress and anxiety levels”. Mr MacKay says in his affidavit: “… I believe that the stress associated with waiting for the resolution of this complaint is affecting Mr. Llanes’ health and work”.

41 Mr. MacKay also states that staff turnover in the restaurant/hospitality industry is high, staff members are transitory, and Cheers has a turnover of almost 75% each year. The Respondents submit that, as a result, witnesses for the Respondents may not be available if the hearing is postponed. Furthermore, they say that the events alleged by Ms. Rostas occurred in 2005, and the memories of witnesses will be impaired with time.

42 On that basis, the Respondents submit that they will be unduly prejudiced by an adjournment of the hearing. I do not agree.

43 Unlike Ms. Rostas, Mr. Lllanes did not submit a physician’s report to support his assertions about the state of his health. Mr. MacKay’s observations about Mr. Llanes’ condition are, at best, speculative and therefore unhelpful.

44 The Respondents’ assertions with respect to their witnesses are also unpersuasive. As noted by Ms. Rostas in her Reply, although her Complaint was filed over a year ago, the Respondents have apparently located nine witnesses in addition to Messrs. Llanes and MacKay. There is no reason to expect that their whereabouts will be lost, or their memories will substantially fade, before the hearing, even if an adjournment is granted. Measures could presumably be taken by the Respondents and their counsel to ensure that contact coordinates are maintained, and witness statements can be recorded to capture their present recollections.

45 I find that no undue prejudice will result to the Respondents by granting the adjournment requested by Ms. Rostas. - Even the discrete point for which the Complainant relies on Rostas is weak. The

Complainant’s cited paragraph of Rostas describes the Rostas complainant as seeking

precisely the kinds of targeted legal representation Mr. Neufeld has sought: legal aid-type

organizations and a sole practitioner who appears to specialize in a certain type of subject

matter. - In the Rostas complainant’s case, those were the BC Human Rights Coalition, CLAS, and

barbara findlay. In Mr. Neufeld’s case, those were the Justice Centre for Constitutional

Freedoms, Freedoms Advocate, the Democracy Fund, and Paul Jaffe. The idea that the

Complainant has somehow shown by way of this isolated paragraph that the Rostas

complainant “assiduously and conscientiously” pursued legal representation and Mr.

Neufeld by comparison did not lacks foundation. Certainly this one cherry-picked

pinpoint does not get the job done. Further, the Rostas tribunal based its decision in part

on the complexity of the case:

32 With respect to the efforts made by Ms. Rostas to obtain legal representation, I note that the reason she offered for making the First Application in July 2006 was that she was then seeking assistance from the Coalition. She was subsequently represented briefly by Ms. findlay, apparently on a pro bono basis, and then by CLAS. Although, for reasons that are not apparent, CLAS did not file a Notice of Appointment until February 2007, Ms. findlay’s October 5 letter, which she copied to Respondents’ counsel, clearly indicates that CLAS had agreed to represent Ms. Rostas in or about early October 2006. This is not a case in which a complainant failed to take active steps to secure legal representation in a timely manner. Ms. Rostas assiduously and conscientiously pursued that

objective.

33 In the matter before me, the particular relevant circumstances include the staffing issues presently confronting the lawyers employed by CLAS. Rather than the usual complement of four, there are currently only one parttime and two full-time lawyers available to represent complainants under

the Code. This has resulted in the unfortunate and difficult dilemma in which Ms. Rostas and her counsel find themselves; a situation for which neither bears responsibility.

34 In addition, in the matter before me, there are two factors which were apparently not before the Tribunal in the cases cited by the Respondents. First is the complexity of the issues and the length of the anticipated proceedings at the hearing. As I have noted, the Complaint is against not one, but three Respondents. The possible liability under the Code of each Respondent will be relevant, both with respect to the evidence adduced at the hearing and with respect to legal issues arising from the evidence. A total of 17 witnesses will be called to give evidence and be subjected to cross-examination. Compared to a more straightforward complaint, the proceedings will be lengthy and complex. - Rostas speaks also to the desirability of parties who are clearly overwhelmed by the process being afforded the opportunity to meet their cases in a just and fair manner. Poorly crafted submissions are not necessarily evidence a party is disengaged or refusing to employ diligence. Sometimes a party is simply unable to cope with the volume of materials and obligations coming at him—evidence that he requires counsel:

36 The Tribunal has often stated that parties before it do not have an absolute right to be represented by counsel (see, for example, Gill v. Cheslatta Forest Products and another, 2005 BCHRT 194 at para. 19; and Allan v. Jones Emery Hargreaves Swan (No. 2), 2005 BCHRT 249, at para.

12). That is so, and many parties, both complainants and respondents, represent themselves in proceedings before the Tribunal; some, with proper preparation, do so very competently and successfully. The Tribunal’s Rules also refer to the facilitation of the just and timely resolution of complaints, which indicates the desirability of scheduling hearings as soon as reasonably practical.

37 However, there are circumstances where the purposes and objectives of the Code, and the overarching requirement that hearing processes be fair, are best served by granting an adjournment so that a party’s interests may be fully and fairly represented at the hearing by counsel. See Weileby v. LaFleur et al, 2006 BCSC 1852 (proceedings under the Manufactured Home Park Tenancy Act, S.B.C. 2002, c. 77 and the Judicial Review Procedure Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 241). In such circumstances, a request for an adjournment will be reasonable. In my view, given the complexity of the pending hearing and the state of Ms. Rostas’ health, this is such a case. I am strengthened in that view by having read the Complaint and other documents prepared by Ms. Rostas while she was self-represented, and having conducted the pre-hearing conference at which I made the decision

to deny the First Application and at which Ms. Rostas represented herself. - Day v BCIT, 1998 BCHRT 29 [Day] is not an answer to the Complainant’s response to

Mr. Neufeld’s adjournment application for several reasons:

- The Complainant both contacted and retained counsel the day before the hearing to show up at the hearing and ask for an adjournment, while the Complainant neither showed up at the hearing nor made herself available to be contacted (at paras 6, 17);

- As late as the first day of said hearing, counsel was unable to confirm that she would be representing the Complainant at the hearing (at para 6);

- Unlike Mr. Neufeld, who has been completely candid about his efforts to retain counsel, including which organizations he has approached and their flat denials of his request, the Day complainant made claims about the unavailability of a local legal aid lawyer to review her file which the Tribunal was able to ascertain were untrue (at para 8);

- The Tribunal states, “Undoubtedly had the application been brought at an earlier time it would have been reasonable to request further medical information, however given that this note has been produced at the last minute there is no reasonable way to get that evidence without adjourning the hearing” (at para 11);

- The prejudice to the respondent was not adjourning, rather “adjourn[ing] at this last minute”, as distinct from the present case wherein the adjournment application was brought a month out (at para 12);

- In contrast to the present case, there was no way of determining whether the hearing could proceed after a short adjournment of certain duration because the very bases of the adjournment could not be resolved with certainty (at para 12);

- Had the Day adjournment application been brought “a week or two weeks ago”, “[m]uch of the prejudice…could have been avoided” (at para 13);

- The imminent nature of the hearing, where the opposing party was “here and ready”—meaning already assembled at the hearing—rendered the adjournment prejudicial (at para 15);

- The last-minute nature of the request, and the forewarning from the Tribunal concerning last- minute adjournment applications: “You should be aware that adjournment applications made at the last minute are difficult to obtain” militated in favour of denying the adjournment (at para 16).

11. Unlike MacGarvie v Friedmann (No. 3), 2007 BCHRT 133 [“MacGarvie”], Mr. Neufeld has explained that between the adjournment granted on May 16, 2024 and September 18, 2024, he had been unable to find a lawyer. Mr. Neufeld explained that he could not afford mainstream and large firms; the pro bono free expression organizations through which he sought to retain counsel denied him representation; and the one BC free speech sole practitioner he found who might represent him in such a matter at a reasonable cost was unable to do so.

12. The Complainant’s claim concerning paragraph 29 of MacGarvie is misleading. Contrary

to counsel’s implied assertion that the respondent in MacGarvie “failed to sufficiently advise the Tribunal of the steps he took” to retain counsel, what MacGarvie actually states is that the respondent had not informed the Tribunal of any steps he had taken to retain counsel (at para 29). Mr. Neufeld has detailed 5 steps he took to retain counsel, beginning with trying to work something out to keep his original counsel. Mr. Kitchen represents Mr. Neufeld’s 6th attempt to retain counsel.

13. The paragraph following the paragraph the Complainant misappropriated further explains that which will become a trend throughout the discussions of the Complainant’s case law going forward and what the Tribunal also eludes to in Day: the MacGarvie matter was becoming fragmented as a result of the many adjournments. Additionally, witnesses were actually becoming difficult to locate and actually losing their memories:

30 Even if Mr. Friedmann’s request had been reasonable, I would not have granted it on the basis that Ms. MacGarvie would be unduly prejudiced by a further adjournment. As indicated in Ms. MacGarvie’s submissions, the hearing into this matter has been delayed several times. The hearing set for October 2005 was adjourned; the hearing set for March and April 2006 had to be discontinued, allegedly due to Mr. Friedmann’s misconduct; the hearing set for July 2006 was adjourned after two days of testimony, due

to Mr. Friedmann’s illness; and the continuation of the hearing set for August 2006 was adjourned because of the Tribunal member’s illness. If Mr. Friedmann’s request were granted, this would, in effect, be the fifth time the matter has been adjourned. I note that none of the previous adjournments, or this current application, were at the request, or were caused by, Ms. MacGarvie. As a result of the delay, witnesses are becoming more difficult to locate, and memories are fading.

31 Ms. MacGarvie made special arrangements to attend the hearing, including missing shifts at work and missing a job interview. For at least the third, and perhaps a fourth time, she has applied to the Tribunal for orders for witnesses to appear. These witnesses have arranged their schedules so that they can attend the hearing. I note that some witnesses had already testified in the earlier hearing and had to be asked to

testify again. Ms. MacGarvie’s counsel made special arrangements and travelled from Alberta to represent Ms. MacGarvie at the hearing. She advises that, if the hearing is adjourned, she will be unavailable to

represent Ms. MacGarvie until the fall at the earliest.

14. The next paragraph the Complainant omitted provides further context to the denial of the MacGarvie respondent’s application for adjournment—being that he brought it on the day of the hearing:

Mr. Friedmann made his application for an adjournment at the beginning of the hearing, rather than filing his application at least two business days before the start of the hearing. He did not explain what information or circumstances forming the basis of the application had come to his attention later, as contemplated by Rule 30(2) and (3). Bringing an application to adjourn at the start of the hearing often means that the other participants and the Tribunal are inconvenienced. Many participants have to travel to attend a hearing or have to miss school or work. As well, Tribunal members could have been assigned to other matters (MacGarvie at para 32).

15. Figliola v BC (Workers’ Compensation Board), 2009 BCHRT 83 [Figliola] is off point. In that case, the Complainant was facing an adjournment of indefinite duration while the Respondent pursued an indefinite number of remedies in a different forum, resulting in fragmentation of the Tribunal process:

The Complainants further submit that because WCB anticipates that the BC Supreme Court’s decision will be appealed, the review process may very well be ongoing, in which case the Tribunal should complete its process instead of granting an adjournment based on anticipated future processes…Counsel for WCB rightly states that he cannot definitively know if he will receive instructions respecting further appeals or judicial review of these Complaints; however, he has indicated that such might be anticipated. I am not persuaded that a further adjournment, sought for an indefinite period of time, while WCB seeks ongoing review of a preliminary decision is sufficient reason for the Tribunal to further delay its process. It is just this kind of fragmentation of the Tribunal’s process that is to be avoided: C.S.W.U. Local 1611 v. SELI Canada and others (No. 4), 2007 BCHRT 442, para. 50 (at paras 24-5).

16. In this light, the penultimate paragraph of Figliola affirms that the indefinite nature of the delay and fragmentation of the case is what would render the adjournment unduly prejudicial. In the present case, the length of delay is not ambiguous, not reliant on an unknown number of proceedings at the BC Supreme Court, and not of the kind which threatens to fragment the Tribunal’s process.

17. Neither does Figliola buttress the Complainant’s assertion that “additional weeks or months of delay are very likely to contribute” to “loss of memory” and “willingness to participate”, much less that “ [i]t is in precisely these circumstances where delay is no longer a matter of ‘expediency’ and results in undue prejudice”. The fact is, Figliola says nothing of the sort.

Complainants Assertions Answered

18. The Complainant complains of insufficient details around the retention of Mr. Kitchen by Mr. Neufeld, but the Complainant was at liberty to cross-examine Mr. Neufeld on the point, which it declined to do despite Mr. Kitchen’s explicit offer of making himself and Mr. Neufeld available for cross-examination. Doubtless the fact Mr. Kitchen created a website in early September significantly increased his visibility such that a person like Mr. Neufeld could find him. The Complainant need only have asked.

19. It is unclear on what basis the Complainant assesses that Mr. Neufeld had “ample time to search for and retain counsel”. All the time in the world is not ample time to retain counsel if no counsel will take the case. Mr. Neufeld wields neither the social clout nor the resources of the Complainant, which would have made all the difference in his ability to retain counsel in the timeframe the Complainant considers ample. But, in Mr. Neufeld’s particular circumstances, finding counsel whom he could afford and who was willing to take his case proved a near insurmountable hurdle.

20. Mr. Neufeld discharged his burden of explaining by way of affidavit evidence whom he approached, the fact that those organizations/lawyers declined to represent him, and when he was finally able to retain present counsel. Again, the Complainant had the right to cross-examine Mr. Neufeld on this evidence to satisfy itself of any facts surrounding his efforts to retain and his ultimate retention of counsel, a right it chose not to exercise.

21. If, as the Complainant asserts, “[t]he timing of his efforts to retain counsel is, in the Complainant’s respectful submission, highly relevant”, the Complainant ought to have exercised its right to cross-examine Mr. Neufeld. That the Complainant waited to assert without evidence in its response to his adjournment application that Mr. Neufeld’s efforts to retain counsel are now “too late to remedy by way of reply” seems rather convenient—for the Complainant.

22. The Complainant points to the insufficiency of Mr. Neufeld’s efforts to retain counsel, but the fact is Mr. Neufeld applied to 5 times the number of organizations/lawyers—6, if Mr. Kitchen is included—as anyone reflected in the Complainant’s exemplar precedents.

23. As the Complainant acknowledges, Guild Yule, a firm that had been representing Mr. Neufeld and was already conversant in his case required a $150,000 retainer. Mr. Neufeld’s likely presumption that any mainstream firm wading in for the first time would command the same or more was eminently reasonable.

24. The Complainant’s statement, “The retainer fee of $150,000 is a significant sum. However, this does not speak to Mr. Neufeld’s ability to retain alternative counsel in the seven months since his previous counsel’s departure” is absurd. The $150,000 retainer required by lawyers who already knew and were somewhat sympathetic to Mr. Neufeld’s plight, having fully informed themselves on the file and what he is up against speaks volumes about Mr. Neufeld’s ability to retain alternative counsel. It tells of any mainstream law firm being financially out of reach for Mr. Neufeld. It tells of the necessity for Mr. Neufeld to seek out organizations which specialize in this particular kind of work, which he did. This one simple statement the Complainant has identified as insignificant contains multitudes.

25. Pretending Mr. Neufeld ought to have contacted every mainstream law firm whose polite lawyers would doubtless bristle at the subject matter of his case, after having already been rejected by the one mainstream law firm that had worked on his case and priced itself out of his reach, is disingenuous.

26. To the Complainant’s further statement that “Mr. Neufeld’s previous loss of counsel and Mr. Bell’s retainer request has already been the basis of one adjournment. Mr. Neufeld cannot rely on Mr. Bell’s departure in February as the basis for yet another adjournment application in September”: the Complainant offers no basis on which the longstanding and continuous problem of Mr. Neufeld being unable to retain counsel invalidates his claim tha the has, in fact, had a continuously difficult time retaining counsel. If anything, the clearly continuous inability of Mr. Neufeld to retain counsel supports Mr. Neufeld’s adjournment application now that he has, after these many months of trying, finally managed to successfully retain counsel.

27. The fact is, Mr. Neufeld approached precisely the appropriate outfits with precisely the reputational intestinal fortitude to take on his case. That they declined is unfortunate, but not his fault.

28. The Complainant’s hair-splitting attempt to distinguish the organizations Mr. Neufeld approached from the sort of “law firms” it opines Mr. Neufeld ought to have approached boils down to the Complainant’s apparent inability to spot a distinction without a difference. The organizations Mr. Neufeld approached and what they do will be the topic of the next section.

29. The Complainant complains that Respondent counsel has not “sought the availability of Complainant counsel” for new hearing dates. It is not Respondent counsel’s practice to begin attempting to coordinate new hearing dates with an opponent who has expressed unwillingness to coordinate new hearing dates by virtue of opposing an adjournment request. Respondent counsel will gladly canvass dates at the hearing of this application and will be prepared to commit to any dates that do not overlap with already-scheduled trials or hearings on which he is counsel.

30. The Complainant complains that “the Respondent has not identified which time periods he might be available or unavailable”; however, Respondent counsel stated in the clearest possible terms that he would make every effort to defer to the availability of Complainant counsel and the Tribunal post 6-week adjournment.

31. The Complainant complains that it has no way of knowing whether the three-member Tribunal panel will be available in six weeks for a two-week hearing; however, it is not as though the Tribunal will be obliged to make its adjournment decision in a vacuum. The Tribunal will be able to immediately determine whether it does or does not have availability, providing full and instant resolution on this point.

32. The Complainant’s statement, “Given Mr. Kitchen’s busy litigation schedule, we would not presume to know when he may have another two-week opening” is disingenuous, since Mr. Kitchen has already stated a) his busy period is the period prior to the conclusion of the would-be six-week adjournment; and b) he will make every effort to be available on the Tribunal’s and opposing counsel’s schedules post 6-week adjournment.

33. The Complainant accuses Mr. Neufeld of obliquely referring to prejudice, before itself obliquely referring to prejudice. The difference is that while it is unclear what undue prejudice the Complainant would suffer from a six-week adjournment, Mr. Neufeld’s prejudice is patently obvious. He has been without counsel for seven months, during which time he has submitted admittedly inadequate submissions and missed deadlines. Unlike the power wielded by the BCTF, Mr. Neufeld enjoys no institutional support. Mr. Neufeld is elderly, not legally trained, and has been unrepresented. ______ _____________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________

34. _________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________

35. The Complainant states that the inquiry is not about counsel and the focus is on the Respondent, before making the inquiry about counsel for the Complainant rather than any prejudice to the Complainant.

36. The Complainant points to no Tribunal precedent supporting the assertion that “repreparing witnesses”, “reviewing evidence for the hearing” or “repeating work” in and of themselves constitute undue prejudice.

37. The rather obvious irony in what counsel for the Complainant argues is she at once believes her client unduly prejudiced by virtue of her own obligation to brush up on material with which she and her client are already familiar, while opining that the Respondent will somehow be less prejudiced by his counsel having not received adequate time to review the material his first time out. It also corroborates the Respondent’s submission that an unusually high amount of preparation is in fact required for this case

due to both the legal complexity and large volume of documentary evidence and anticipated witness testimony. Additionally, the position that extra work for counsel constitutes undue prejudice directly contradicts the Complainant’s position that the focus is not on counsel.

38. The Complainant admits that it “can likely cancel planned leaves of absence for laywitnesses and expert witness time without incurring too much extra expense”. The real problem the Complainant identifies is that it lacks “any assurance the adjournment will actually be of short duration”. This is nonsensical. The Tribunal is at liberty to provide such assurance by scheduling the hearing in accordance with the short adjournment the Respondent seeks.

39. It is no answer to say “there is no question that delaying this hearing yet again will amount to undue prejudice for the Complainant”, when the Complainant has offered no legally supported reason any undue prejudice would be visited upon it. The Complainant has offered no evidence that any individual witness will lose his or her memory or lose his or her willingness to participate. This is what the Tribunal has called “speculative” prejudice, as the Respondent pointed out in his application to adjourn.

Free Speech Organizations Providing Pro Bono Legal Representation

40. The Complainant’s assertions that the organizations Mr. Neufeld approached are not law firms or deal only with pandemic-related cases and therefore ought not be considered part of his efforts to retain counsel is grasping, to say the least. A cursory glance would have revealed to the Complainant these organizations operate almost exactly the way CLAS does; they simply do not take government money to do it. Further, simply clicking on a tab which reads “What we do”—or some similar invitation—reveals the provision of legal representation to numerous pro bono clients in the precise area in which Mr. Neufeld requires representation (human rights, free expression, Charter law, administrative law (upon appeal), et cetera).

41. Cherry picking from a website three descriptions in an effort to pretend Mr. Neufeld was not in the right place is, frankly, misleading.

42. The following list contains just some of the clients and cases for whom and which these three organizations have provided the services of lawyers, all accessible in the same place the Complainant found its misleading characterisations. The Respondent will be happy to provide this evidence in affidavit form if the Complainant desires or the Tribunal finds it necessary. It should be noted that Respondent counsel is intimately familiar with these organizations and many of these cases, having directly worked on some of the cases and having been an in-house lawyer for one of the organizations up until 2021.

The Democracy Fund

- VICTORY: Meghan Murphy speaking event to proceed

- “Cancelled” author Meghan Murphy and TDF fight to ensure free speech rights are respected

- Pastor Reimer acquitted of all charges related to protest against Drag Queen Story Hour in Calgary

- Anti-prayer bylaw charges dismissed against Pastor Derek Reimer

- TDF expresses concern over federal government’s new censorship bill

- TDF tells City of London to reject by-law amendment targeting pro-life expression

- Government abandons legislation censoring “dis/misinformation”

- TDF and James Kitchen Defend School Board Trustee Monique LaGrange

- TDF wins appeal for man who received criminal record as a result of Windsor protest

- TDF represents Dr. Hodkinson in misconduct hearing over COVID statements

- TDF successfully defends man charged after filming police station from sidewalk

- Crown withdraws all charges against peaceful protester arrested, Tasered at Ottawa protest

- Calgary withdraws charges in anti-free speech transit by-law case

- TDF defends the rights of transit users against anti-free speech transit bylaw

- No discipline for Ontario teacher accused of failing to use pronouns in classroom

- TDF fights to uphold the right of free expression by defending teenager accused of inciting hatred

- Ontario teacher Chanel Pfahl retains her teaching certificate

Freedoms Advocate

- Regina Civic Awareness and Action Network (RCAAN) (Legal support to an intervenor in UR Pride Centre v Government of Saskatchewan, et al, KBG-RG-01978-2023);

- Emanuel Student Discriminated Against by Anti-discrimination Services;

- Zaki v. University of Manitoba;

Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms

- Parent and gender dysphoria groups granted intervenor status in New Brunswick school policy case;

- Nurse faces suspension after endorsing safe spaces for biological females;

- Quebec teacher challenges gender transition policy in case about compelled speech and freedom of conscience;

- Edmonton denies prolife organization booth at KDays in violation of Charter;

- Ontario man fights back after Ministry of Transportation censors his billboard;

- Transsexual and parent groups support children’s rights in SK court case;

- Challenging expanding definitions of “hate speech” in Canada;

- Teacher silenced for raising concerns about age-inappropriate books;

- Transgender person with male genitals sues female beauty pageant for refusing service (Yaniv v. Canada Galaxy Pageants)

Next Hearing Date:

On May 21 the BCHRT said they would deliver their decision within the next six months.

It was announced that they will not deliver until Jan/Feb 2026.

Consider a Donation

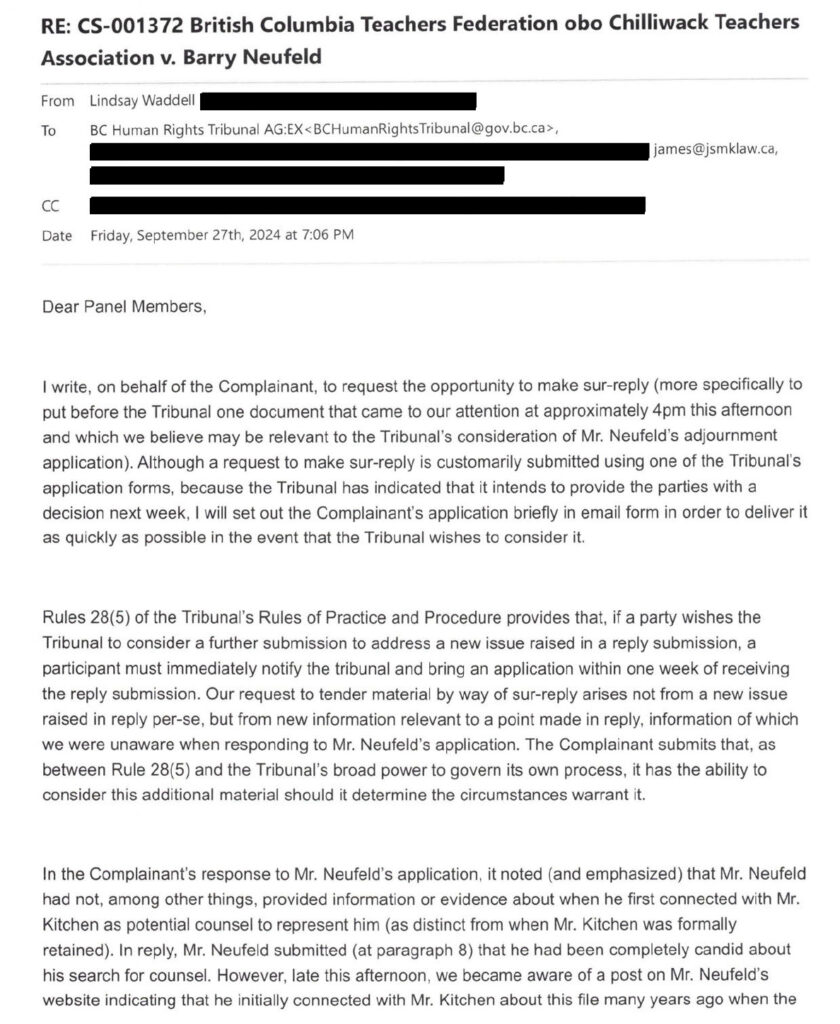

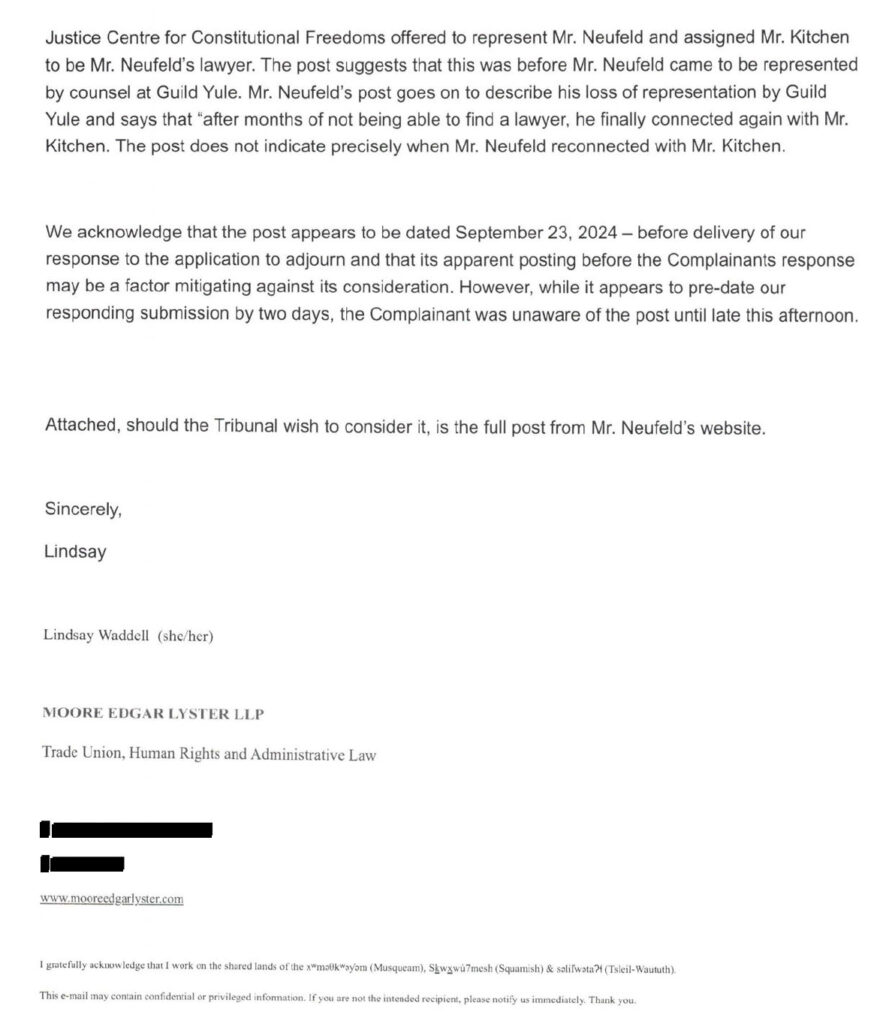

Letter Drafted In Response To The Complainant’s Lawyer’s Email Of Friday Evening

(Sept. 27)

JAMES SM KITCHEN

Barrister & Solicitor

203-304 Main St S, Suite 224

Airdrie, AB T4B 3C3

587-330-0893

james@jsmklaw.ca

September 30, 2024

VIA EMAIL

BC Human Rights Tribunal

1270 – 605 Robson Street

Vancouver, BC V6B 5J3

Attention: Devyn Cousineau, Tribunal Member

Ijeamaka Anika, Tribunal Member

Robin Dean, Tribunal Member

Dear Panel Members:

RE: BCTF obo CTA v Barry Neufeld, BCHRT Case No. CS-001372 – Counsel email of September 27, 2024

At 6:06 PM PDT on Friday, September 27, 2024 I received the enclosed email, on which I was copied, sent by counsel for the Complainant to the Tribunal. Counsel had not contacted me prior to this email to alert me of her concern, such as it is.

The substantive content of counsel’s email amounts to much ado about nothing, yet the communication

demands a response because of its inappropriate nature. The underlying suggestion of counsel’s email is

that my client and I have engaged in some sort of imagined secret shenanigans, a suggestion that is, of

course, scandalous and unbecoming.

The Content of the Improper Email

The email’s first paragraph purports to “request the opportunity to make sur-reply” before segueing to an

obfuscatory explanation of the supposed rules on point and the supposed facts of the matter. The second

paragraph of the email sets out the Rule 28(5) exception to the Rule 28(4) restriction on further submissions, being “to address a new issue raised in a reply submission”, before admitting that the Complainant’s wish to make sur-reply does not fit into the Rule 28(5) exception.

The fourth paragraph of the email admits that the Complainant’s wish to make sur-reply does not fit into

the Rule 28(6) exception either, since the information the Complainant sought to disclose by way of surreply had been discoverable prior to the Complainant filing its response to the Respondent’s adjournment application.

For further certainty, the Complainant admits in its email purporting to “request the opportunity to make

sur-reply” that its “request” fits neither of the exceptions to the Rule 28(4) restriction on further submissions, whether explicitly, implicitly, or both.

Nevertheless, in the third paragraph of the Complainant’s “request” to make further submissions, absent any rule that would permit the Complainant to make further submissions, the Complainant spontaneously

launches into further “submissions”, calling into question Mr. Neufeld’s candour concerning his search for counsel and his truthfulness in declaring his candour concerning his search for counsel, on the basis of a post on Mr. Neufeld’s website indicating that he had been connected with me, in the words of the email,

“many years ago when the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms offered to represent Mr. Neufeld

and assigned Mr. Kitchen”—an accusation which necessarily extends to me, since I am Mr. Neufeld’s

counsel, and Mr. Neufeld’s alleged ploy would be unsustainable were I not working in concert with him.

The oddest feature of the Complainant’s email is that, while it clearly seeks to cast aspersions on the

Respondent and his counsel, it is difficult to make out the precise object of the Complainant’s fixation; it

appears to be the fact that in 2018, while still a first year call, I was the junior assigned by the Justice

Centre for Constitutional Freedoms to Mr. Neufeld’s file, after which, approximately two months later,

the Centre closed the file and Mr. Neufeld moved on to the private-practice law firm his professional

liability insurer provided.

Whatever the Complainant’s protestation in this regard, which is not entirely clear, it bears noting that

prior to filing its response to the Respondent’s adjournment application, the Complainant had both a right to cross-examine Mr. Neufeld on his affidavit, and an explicit invitation extended by Respondent counsel to do so. The Complainant declined to exercise its right to cross-examine Mr. Neufeld. Having done so, the Complainant is not now entitled to cast unfounded aspersions before the Tribunal.

For the reasons set out herein, the Respondent submits that the Tribunal should:

- Decline to receive any further material from the Complainant regarding the Respondent’s

Application for an adjournment; and - Direct a case conference be held on or before October 2, 2024 to address any outstanding matters

and hear directly from counsel for the parties.

The Relevant Rule

Rule 28(4) of the BC Human Rights Tribunal Rules of Practice and Procedure (“Rules”) reads: “The tribunal will not consider submissions other than those permitted in a schedule for submissions, unless it allows an application under rule 28(5) or (6)”. [Emphasis added.]

Rule 28(5) permits a party to request that the Tribunal consider a further submission “to address a new issue raised in a reply submission”. Rule 28(6) permits a party to request that the Tribunal consider a further submission “to address new information not available to the participant when they filed their submission”. [Emphasis added.] Neither the Rule 28(5) exception nor the Rule 28(6) exception is presently in play.

The Complainant first attempts to transform these two rules into some sort of mutant rule approximating “The Respondent didn’t bring up anything new in his reply, but something in there made me think of something new, so it’s new”. That, of course, is not how this works.

The Complainant next attempts to cobble together the Tribunal’s “broad power to govern its own process” with half of Rule 28(6)—the whole of which the Tribunal doubtless made as part of its broad power to govern its own process—resulting in another invented chimera rule that would have this Tribunal ignore any part of the rule which fails to serve the Complainant.

The Complainant’s claim, “Our request to tender material by way of sur-reply arises not from a new issue raised in reply per-se, but from new information relevant to a point made in reply”, is both false and misleading. The “new information” to which the Complainant refers is not new information pursuant to the definition of new information in Rule 28(6), which contemplates new information “not available to the participant when they filed their submission”. Two paragraphs on, the Complainant “acknowledges” that the information was available before it filed its response to the adjournment application.

Notably, “fairness” is not a consideration independent of the requirements of the Rule 28 test for accepting further submissions, being a new issue or new information, as defined in the rule. Umolo v

Manchanda Corp Ltd (cob Shoppers Drug Mart), 2021 BCHRT 166 decides that fairness is the third of

three requirements:

[T]he Tribunal only permits sur-replies when all of the criteria in Rule 28 are met:

(1) new issues or information are raised in the reply submissions of another party;

(2) the new information was not available to party when they made their own submission;

and

(3) fairness requires that the Tribunal consider the further submission: Rule 28(6).

I agree with Shoppers that Mr. Umolo raised new issues and information in his reply, about the reasons for his delay, including: the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, and a family member’s illness [the New Information]. The New Information was not available to the Respondents when they filed their responses. If the New Information had any bearing on my decision in this matter, fairness would require that I accept and consider Shoppers’s sur-reply. However, I have not found it necessary to consider the New Information in arriving at this decision. As a result, I do not accept this New Information raised in Mr. Umolo’s Reply. Therefore, I assess Mr. Umolo’s late-filed complaint without taking into account the New Information provided in Mr. Umolo’s reply, or Shoppers’s sur-reply (at paras 20-1). [Emphasis added.]

Accordingly, more is required than is reflected in the Complainant’s submission that the Tribunal “has the ability to consider this additional material should it determine the circumstances warrant it”. The Rules are clear about the circumstances that warrant the Tribunal’s consideration of additional material, as is the case law.

The Tribunal Precedents on the Rule

Numerous BCHRT cases reflect the tripartite test for determining whether the Tribunal should accept

further submissions, with the first two factors being (1) new issues or information which were (2) unknown or unavailable, and the final factor being (3) “fairness”, which determines whether such new

issues or information will be considered: Pereira v Corporate Classics Caterers, 2015 BCHRT 31 [Pereira] at para 35; Pearson v JV Logging Ltd, 2020 BCHRT 5 at para 21; Ali v North Peace Seniors

Housing Society, 2017 BCHRT 88 [Ali] at para 20; Minasyan v Strata Plan LMS 3845, 2015 BCHRT 134

at para 13; Broe v Board of Education of School District No 67 (Okanagan Skaha), 2023 BCHRT 157 at

paras 25-6; C v Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, 2021 BCHRT 22 at para 45; Humphrey v BL Resort Ltd, 2023 BCHRT 195 [Humphrey] at para 7; Malhi v Langara Students’ Union Assn, 2018 BCHRT 64 at para 11; Patrick v British Columbia (Emergency Health Services), 2024 BCHRT 124 at para 60; Shachak v Doctor Rahil Faruqi Inc, 2015 BCHRT 55 at para 19; Shahgou v Strata Plan No BCS 3495S, 2024 BCHRT 176 at para 18; Simpkin v Stl’atl’imx Tribal Police Board, 2014 BCHRT 255 at para 20; Singh v Prime Deals International Ltd, 2024 BCHRT 161 at para 23.

Information must be legitimately undiscoverable prior to submissions in order to be “new” within the

meaning of the rule—for example, a freshly released decision: Pereira at para 37; Ali at para 23;

Humphrey at para 7. Even where information is new, it will only be considered if it is also relevant:

Emslie v Lululemon Athletica Canada Inc, 2024 BCHRT 41 at para 13.

Where the Tribunal has expressed a willingness to depart from the Rule 28(5) and (6) criteria, some

exceptional circumstance has factored into the Tribunal’s reasoning, such as Tribunal error (Alexander v Saanich (District), 2019 BCHRT 82 at paras 17-8); a self-represented party (Thejoisworo v Northern Gold Foods Ltd, 2021 BCHRT 121 at paras 63-4; Deboo v British Columbia (Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General), 2018 BCHRT 10 at para 127; SL v Michell’s Farm Market Ltd, 2024 BCHRT 54 at

paras 33-4); a decision so overwhelmingly weighted against the party seeking to enter the submission, the Tribunal undertakes, as something of a formality, to ensure it has left no stone unturned (AB v City, 2024 BCHRT 196 at para 29; Bruintjes v North Central Plumbing & Heating Ltd, 2023 BCHRT 162 at para 26; Colbert v North Vancouver (District), 2018 BCHRT 40 at para 10); or a correction to information previously given to the Tribunal, as outlined in Woollacott v Canadian Forest Products and another, 2014 BCHRT 61:

[25] The overriding consideration is whether fairness requires an opportunity for further submissions. The circumstance specifically addressed in Rule 24(6) and (7), where new issues have been raised in reply, is one where fairness may require such an opportunity. There are others, as described in Gichuru v. The Law Society of British Columbia (No. 2), 2006 BCHRT 201:

As explained in the Kruger decision, the justification for permitting a sur-reply is fairness. In the vast majority of cases, this will be because new matters have been raised in reply and fairness requires that the other party be given an opportunity to respond. This consideration does not apply here.

It is possible that a sur-reply might be allowed in other situations, i.e., to correct incorrect information previously given to the Tribunal. As well, I do not wish to foreclose the possibility that, in an appropriate case, new evidence might form the basis for a sur-reply. (paras. 21-22)

The Irrelevance of the Information in Any Event

The foregoing are the technical problems which are alone fatal to the Complainant’s request. However, even were Rule 28(6) in play, which it is not, because the information to which the Complainant refers was “available to the participant when they filed their submission”, leaving it outside the Rule 28(6) exception, there is no probative value in the information the Complainant seeks to place before the Tribunal. The information the Complainant has sleuthed simply in no way assists the Complainant. First, the Complainant states by way of Complainant counsel’s September 27th email, “In reply, Mr. Neufeld submitted (at paragraph 8) that he had been completely candid about his search for counsel”. The pinpoint to which counsel refers, here reproduced, does not appear to disclose what the Complainant claims it discloses:

In the Rostas complainant’s case, those were the BC Human Rights Coalition, CLAS, and barbara findlay. In Mr. Neufeld’s case, those were the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms, Freedoms Advocate, the Democracy Fund, and Paul Jaffe. The idea that the Complainant has somehow shown by way of this isolated paragraph that the Rostas complainant “assiduously and conscientiously” pursued legal representation and Mr. Neufeld by comparison did not lacks foundation. Certainly this one cherry-picked pinpoint does not get the job done. Further, the Rostas tribunal based its decision in part on the complexity of the case:

32 With respect to the efforts made by Ms. Rostas to obtain legal representation, I note that the reason she offered for making the First Application in July 2006 was that she was then seeking assistance from the Coalition. She was subsequently represented briefly by Ms. findlay, apparently on a pro bono basis, and then by CLAS. Although, for reasons that are not apparent, CLAS did not file a Notice of Appointment until February 2007, Ms. findlay’s October 5 letter, which she copied to Respondents’ counsel, clearly indicates that CLAS had agreed to represent Ms. Rostas in or about early October 2006. This is not a case in which a complainant failed to take active steps to secure legal representation in a timely manner. Ms. Rostas assiduously and conscientiously pursued that objective.

33 In the matter before me, the particular relevant circumstances include the staffing issues presently confronting the lawyers employed by CLAS. Rather than the usual complement of four, there are currently only one part-time and two full-time lawyers available to represent complainants under the Code. This has resulted in the unfortunate and difficult dilemma in which Ms. Rostas and her counsel find themselves; a situation for which neither bears responsibility.

34 In addition, in the matter before me, there are two factors which were apparently not before the Tribunal in the cases cited by the Respondents. First is the complexity of the issues and the length of the anticipated proceedings at the hearing. As I have noted, the Complaint is against not one, but three Respondents. The possible liability under the Code of each Respondent will be relevant, both with respect to the evidence adduced at the hearing and with respect to legal issues arising from the evidence. A total of 17 witnesses will be called to give evidence and be subjected to cross-examination. Compared to a more straightforward complaint, the proceedings will be lengthy and

complex.

But whatever the Complainant is referencing, the fact is, Mr. Neufeld did not claim he had never heard of Mr. Kitchen or met Mr. Kitchen in the past. In fact, Mr. Neufeld outright declared in his reply submission that Mr. Kitchen has both worked on cases for the organizations Mr. Neufeld approached for legal representation, and that Mr. Kitchen had served as in-house counsel at one of them. Announcing these facts in one’s reply submission would have been an odd tack were secrecy the objective.

In any event, the Complainant’s information has no bearing on the adjournment application. For a clear understanding of the rare situation in which Mr. Kitchen now finds himself vis-à-vis Mr. Neufeld, consider the unlikelihood of a former CLAS lawyer who enters private practice rubbing shoulders with or trawling for business among the impecunious clients he or she had represented seven years earlier while at CLAS, and vice versa. Legal aid is a world apart from private practice. Moreover, Mr. Kitchen is out of-province. Once Mr. Kitchen launched a website identifying both experience in, and a willingness to take on, certain kinds of human rights cases, people who would otherwise not have availed themselves of Mr. Kitchen’s services have contacted him. As Mr. Neufeld pointed out at paragraph 18 of his reply submission, Mr. Kitchen was not on his radar until September of this year:

The Complainant complains of insufficient details around the retention of Mr. Kitchen by Mr. Neufeld, but the Complainant was at liberty to cross-examine Mr. Neufeld on the point, which it declined to do despite Mr. Kitchen’s explicit offer of making himself and Mr. Neufeld available for cross-examination. Doubtless the fact Mr. Kitchen created a website in early September significantly increased his visibility such that a person like Mr. Neufeld could find him. The Complainant need only have asked.

The larger point, as noted in reply, is that the Complainant was at liberty to cross examine on any

or all of these points and details, and chose not to exercise its right to do so.

Paradoxically, the same Complainant that wants to eliminate from the adjournment equation the time period between Guild Yule LLP’s withdrawal as Mr. Neufeld’s counsel and his June 2024 application to adjourn evidently wants to travel back in time to make an issue of Mr. Kitchen’s early career in public interest law to see if it can unearth a cudgel with which to beat Mr. Neufeld on an adjournment application. This is unseemly, to say the least.

Finally, Mr. Neufeld has concerns with the underhanded way in which the Complainant has sought to

bring its request: after close of business on a long-weekend Friday, absent the proper forms, and in

disregard of the rules detailing the only bases for such requests and the prescribed method by which they are to be brought.

Even had the Complainant been able to satisfy the Rule 28(6) prerequisite for its request—“new

information not available to the participant when they filed their submission”—Rule 28(6)(c) and Rule 28(6)(d) specify that the proper method of submitting the request is to “state in the application when the new information came to the participant’s attention and why fairness requires that the tribunal consider the submission and new information” and “attach the submission and new information to the application”.

Rule 28(6)(d) contemplates attaching the submission and new information to the application, as distinct from using the application process—let alone an email—to disclose potentially prejudicial material before the Tribunal has even had an opportunity to consider whether viewing the material is appropriate. The proper procedure preserves the integrity of the Tribunal’s process.

Rule 28(6) does not contemplate blurting out in an email unsolicited information, to say nothing of groundless accusations, ensuring that irrespective of whether the Tribunal considers the application for further submissions, it will not be able to unsee the implicit disparagement of the Respondent and his counsel.

Rule 28(6) makes a clear distinction between how the fact of information is disclosed and how information itself is disclosed. It appears the Complainant has attempted an end run around the rule

precisely because it knows it does not satisfy the criteria for bringing the application.

The BCHRT’s own discussion in its “General applications” section entitled “GA8: File a further submission on application” provides the following easy to understand primer of the proper process and the legal test for asking to make further submissions:

What are “further submissions”

Submissions are a participant’s arguments and evidence.

When a participant applies for an order, the Tribunal may set dates for:

- the other participants to respond

- the participant who made the request to reply.

Usually, the Tribunal will not allow more “submissions”. Everyone has had their say. The

process would go on and on if participants keep adding new points or evidence.

You must apply to give the Tribunal more arguments or evidence.

Deadline to apply

There is a deadline to apply after: - you receive a reply submission and want to respond to something new in it

- you get new information you want to give the Tribunal

Immediately: Tell the Tribunal and other participants that you are going to apply. Tell them by phone or in writing. Within one week: Apply.

How to apply

When you apply to file a further submission on an application, you must attach the

further submission.

Legal test for making a further submission

You must show three things:

- Something new in the submission or new information

- Your further submission only responds to what is new

- It would be unfair if you couldn’t respond

1. New issue or information

If you want to respond to a point in a submission, explain:

- The new point is not in the other participant’s earlier submission

- The new point is not in your earlier submission

- Why you couldn’t have dealt with the point in your earlier submission

If you want to give the Tribunal new information, explain: - How you just learned of the information

- Why you couldn’t give it with your earlier submission

2. Submission limited to what is new

You must attach your further submission to your application.

Explain that you are only responding to a new point or giving the new information

Do not repeat your earlier submission or talk about other things.

3. Fairness

Explain why it would be unfair if you can’t make a further submission.

How is the new point or information important to the application?

[Emphasis added.]

Sur-reply should rarely be granted and should not be granted in this situation.1 The Complainant had a right to cross-examine Mr. Neufeld, which it declined. The information to which the Complainant refers was discoverable prior to the submission of its response to Mr. Neufeld’s adjournment application. The

1 Chopra et al. v Treasury Board (Department of Health), 2011 PSLRB 99 at para 1: “…the grievors requested an opportunity to make a sur-reply to the employer’s reply submissions. I have determined that there is no requirement for a sur-reply. Sur-reply should only be allowed in the rarest of cases. Sur-reply is not appropriate when a party wishes to clarify the record, respond to attacks on credibility, or respond to the mischaracterization of evidence or submissions.” [Emphasis added.]

date Mr. Neufeld was connected with Mr. Kitchen during the latter’s in-house tenure at a pro bono organization “many years ago” is irrelevant. The only relevant date is the date Mr. Kitchen was retained

as counsel for Mr. Neufeld, which was September 18. Even had the Complainant satisfied the conditions

for bringing this application pursuant to Rule 28, there is no probative value to this inquiry and therefore

no justification for permitting it.

In any event, an unsolicited communication containing no information which can properly be called

“new”, accusing the Respondent and his lawyer of something not quite defined but meant to convey something unseemly, transmitted to the Tribunal on the pretense of constituting an application, on the

basis of a rule the Complainant admits does not apply, on the Friday evening of a long weekend, with the

explicit suggestion that the Tribunal might “wish to consider it” is highly inappropriate and potentially

prejudicial.

There is simply no justification for the Complainant emailing an overwrought note teeming with what amounts to irrelevant gossip, groundless accusations of Respondent and/or counsel impropriety, deceptive representations of the rules on point, and an entreaty to the Tribunal to essentially ignore those rules and consider the irrelevant information and groundless accusations over the holiday weekend, since its decision is due next week, in order to gain an advantage over its opponent. This is far more than a Rule 4(6) technical defect or irregularity in form; this is a tactical decision in an effort to ensure Mr. Neufeld is unsuccessful on his adjournment application and therefore has inadequate representation on the merits of his case. It is not the type of behaviour I expect from an institutional client with experienced counsel.

Should this type of improper conduct persist, it will be met with an application for costs.

Regards,

James SM Kitchen

Barrister & Solicitor

Counsel for Barry Neufeld

Enclosure

Next Hearing Date:

On May 21 the BCHRT said they would deliver their decision within the next six months.

It was announced that they will not deliver until Jan/Feb 2026.

Consider a Donation